Our Civil War

People, especially Southerners, argue amongst themselves over the essential commonality of the “War of Yankee Aggression” (a.k.a. “The Late Unpleasantness” or the “American Civil War”).

Some deny that the war was about slavery whilst others declare slavery the reason for the war.

Okay, let’s look at this thing…

Antietam Battlefield - Dunker Church

Antietam Battlefield - Dunker Church

Common Causes

Those who deny the primacy of slavery (or, as it was then called in polite circles, African slavery1), usually cite these as causes for Southern secession:

- Federal expenditure of Treasury funds for internal improvements within—disproportionately within—states

- Federal tariffs that favored Northern industrial interests at the expense of Southern agricultural interests

- Federal Navigation Laws and fishing bounties that were unfavorable to the South and Southern interests

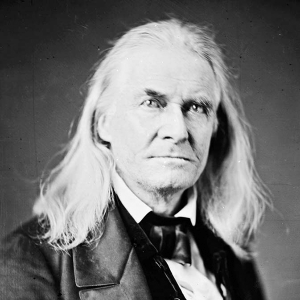

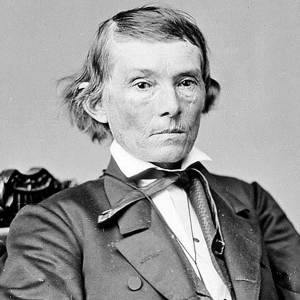

Alexander H. Stephens disputed each of these points in a speech to the legislature at a secession session called by Governor Joe Brown.

What Did Southern Firebrands Say?

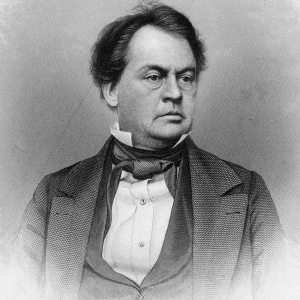

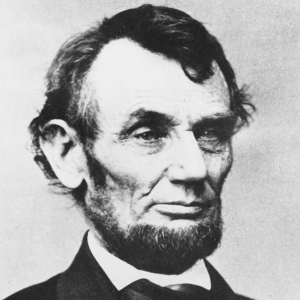

Stephens gave his speech in rebuttal to that presented the previous evening, on November 13, 1861, by Robert A. Toombs. Stephens, in his speech, pointed out that Toombs “…asks if we would submit to Black Republican rule.” In fact, that phrase—Black Republican—was an epithet often hurled at abolitionists and Republicans in general following the election of Abraham Lincoln. Why? Were blacks in power in the Republican Party?

Hardly.

Another charge laid by Toombs against the Union (and answered by Stephens) were laws passed by various New England states to not enforce, or nullify, the Fugitive Slave Act. 2(Oops! There’s that “S” word, again…)

The Cornerstone Speech

Alexander Stephens, who argued against secession, ultimately became the first (and only) Vice President of the Confederate States of America. The Georgia legislature called a Secession Convention and, of course, seceded from the Union. Stephens, who had argued to let the people decide, apparently felt that the citizens of his state had decided and went in with them. On March 12, 1861, Stephens gave a speech in Charleston, SC defending secession, the Confederacy, and the Confederate Constitution. His speech, commonly known today as the Cornerstone Speech, included these assertions:

“But not to be tedious in enumerating the numerous changes for the better, allow me to allude to one other—though last, not least. The new constitution has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution—African slavery as it exists amongst us—the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution…Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests upon the great truth, that the negro [sic] is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth…”

Alexander Stephens, by the way, was a friend of Abraham Lincoln.

Republicans and Slavery

Southern firebrands saw Lincoln and the Republicans, especially William H. Seward, as agents of Northern abolitionists who would, as quickly as they could, render slavery illegal within the United States. This allegation was made so often that the explanation of the term was not needed to be spoken.

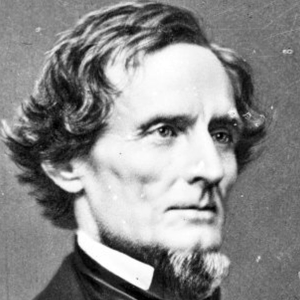

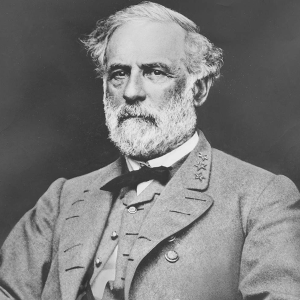

Of course, Lincoln was far from moving to ban slavery. His interest, borne out by his actions, was in preserving the Union, the United States. In the context and course of the resulting Civil War, Lincoln moved very slowly against the “peculiar institution” itself; his administration at first repudiated General John C. Frémont’s order emancipating slaves in Missouri in 1861. (Lincoln relieved Frémont of his command and revoked the order.)

At Fortress Monroe in Virginia, General Benjamin Butler got around this by declaring as “contraband” fugitive slaves who gathered there for freedom and federal protection.

By late 1862, Lincoln believed that he had to do something to more effectively re-mobilize the remaining US states to support the war and to remove the possibility of English and French intervention on behalf of the Confederacy.

So, following the bloody battle of Antietam, the President issued the famed Emancipation Proclamation, in which he declared that:

“…on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free…”

You note, of course, that the Proclamation did not apply to slaves held as property within any state not in rebellion. Why not? Was Lincoln absurdly cynical? Perhaps. But, the President had not the authority to inhibit the accumulation, exercise, or private property within states which were loyal and represented in Congress. The Fifth Amendment states that:

“No person shall be…deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law…”

Only Congress could pass an amendment affecting that, and it could only become law only after the required number of states ratified it—which is why we have the Thirteenth Amendment and it is why that Amendment was introduced and passed by Congress in 1865 during the Civil War.

Was Slavery THE Reason for The War?

No. I think that the war can be laid to these initial reasons:

- Clearly, Lincoln initially sought to prevent secession and preserve the Union.

- Clearly, for the Southern political elite, secession was primarily about slavery.

- It seems, from the sources available, that many Union citizens were initially glad to be rid of the South. The Southern attack on Fort Sumter and their flag, however, changed that feeling.

- Most Southern soldiers saw Northern invasion as a threat against hearth and home.

As the war continued and casualties mounted, opinions and positions hardened. Soldiers whose friends are slaughtered on field after field continue fighting for themselves and their remaining comrades. Political leaders who have so much for which to answer for the conduct of war press further to finish the business. But, the fuse to the powder keg that exploded into our Civil War was slavery.

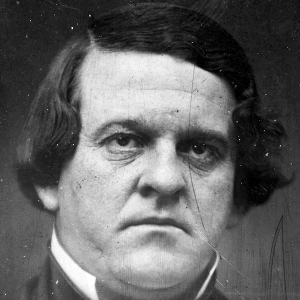

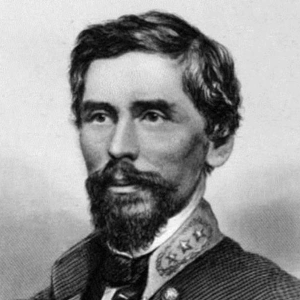

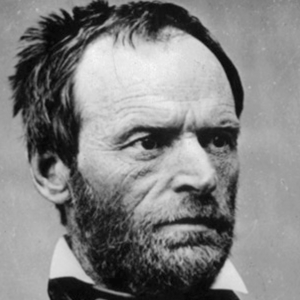

Confederate General Patrick Cleburne, a native of Ireland who emigrated to Arkansas and worked in Helena as a pharmacist, wrote this about the war and its aftermath, as he foresaw it:

“Every man should endeavor to understand the meaning of subjugation before it is too late…It means the history of this heroic struggle will be written by the enemy; that our youth will be trained by Northern schoolteachers; will learn from Northern school books their version of the war; will be impressed by the influences of history and education to regard our gallant dead as traitors, and our maimed veterans as fit objects for derision…The conqueror’s policy is to divide the conquered into factions and stir up animosity among them…It is said slavery is all we are fighting for, and if we give it up we give up all. Even if this were true, which we deny, slavery is not all our enemies are fighting for. It is merely the pretense to establish sectional superiority and a more centralized form of government, and to deprive us of our rights and liberties.”

Cleburne never owned slaves and was more than open to their emancipation…by the Confederate government.3

In the heat of early 1861, many Southern youth flocked to join units; so many that, in many cases, states such as North Carolina had to turn many away because they had no means of supplying them. Why this ardor was so strong (and so well evoked in the famous barbecue scene in Gone With The Wind) is another matter. I just find it impossible to believe that the eagerness of so many—who had never owned and had no means of owning a slave—to enlist was motivated by a desire to protect the institution that separated them from the wealthy planters. Indeed, many Confederate soldiers deserted their units when letters from home spoke of the plight of their families. (Many of these returned to the armies, later.)

Opposition to Confederate conscription laws was strong and bitter amongst the yeomanry because those laws exempted planters and their slave overseers. (On the other hand, Southern states resisted conscription laws because they felt the law abrogated the principle of states’ rights, despite what the Confederate Constitution said about the primacy of national law.)

Oh, By The Way…

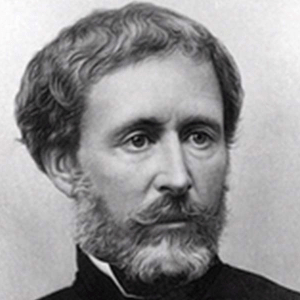

Toombs closed his speech to the Georgia legislature with these stirring words:

“Make my name infamous forever, if you will, but save Georgia. I have pointed out your wrongs, your danger, your duty. You have claimed nothing but that rights be respected and that justice be done. Emblazon it on your banner—fight for it, win it, or perish in the effort.”

He did not live by those words, though. In April of 1865, Toombs’s wife delayed Union cavalry who came to arrest him at his home in Washington, Georgia while he ran out the back and fled on horseback. In November 1865, he landed first in Cuba before going on to England, France, and Canada. Robert Toombs did not return to his home until 1867. He never requested a pardon from the US Congress and his citizenship was never restored. He did, however, conduct a lucrative law practice until his death in December of 1885.

On the other hand, Alexander Stephens awaited arrest at his home near Crawfordville, Georgia. He was taken first to Fort Monroe (where Jefferson Davis was incarcerated) and then to Boston, where he lived in relative comfort until his release. He was pardoned and his citizenship restored; Stephens subsequently served in the US House of Representatives and as Governor of Georgia after Reconstruction. Alexander Stephens died in office as Governor.

A Personal Note

If you’re wondering about me, I was born very much south of the Mason-Dixon line: I’m a native Tar Heel, whose state gave far more of her men to soldier for the Confederacy, proportionately, than any other Confederate state. I eat grits with red-eye gravy without apology, and I am quite fond of the chili dogs served up by The Varsity in Atlanta, GA. I don’t equate either Jefferson Davis or Abraham Lincoln with Hitler, and I am quite happy to be a citizen of the United States.

Notes

(1) No Africans had been brought into the United States to be slaves since 1806.

(2) What makes the actions of those New England states all the more interesting is that the “right” of states to nullify federal law had been decisively rejected in 1833. Then, South Carolina passed an Ordinance of Nullification against the federal tariff acts of 1828 and 1832. Andrew Jackson believed nullification to be treason, and Congress passed a Force Act (1833) authorizing the President to use violence to enforce US law. The crisis was defused when Congress reduced the tariff and South Carolina repealed the Ordinance of Nullification.

(3) In late 1864, General Cleburne wrote a letter to General Joseph Johnston, commanding the Confederate Army of Tennessee in north Georgia and to Jefferson Davis in which he advocated the recruitment of Blacks as Confederate soldiers. He acknowledged that this would require emancipation of the slaves (for who would fight for a nation that held him as chattel?). Johnston agreed that this would solve the Confederacy’s manpower problem, but urged Cleburne not to forward his letter to the government. Cleburne did, and Davis had it suppressed. Patrick Cleburne continued his service until his death at the battle of Franklin, Tennessee in 1864.